The last iron-hammer-works in the Spessart

( Living history between forge and water-wheel )

If you hike from the village of Hasloch into the Spessart, then you can hear from time to time

the metallic knocking of the iron-hammer-works. It is the last iron-hammer-works in the Spessart that still today

can be operated as a

»hydro-power station« with its technical installation dating back to the founding period (year of construction 1779).

This hammer-works is the beginning of the iron factory Kurtz in Hasloch am Main.

Its creation owes the hammer-works to the abundance of trees found in the nearby forests and the waterpower supplied by the

Haselbach (hazel creek), which originates in the Spessart beneath Rohrbrunn. This area formerly

belonged to the Electors of Mainz, who had planned some sort of industrializing of the remote areas of the Spessart

and the Odenwald. Initially, they developed the glassworks which required an immense quantity of wood and charcoal

to operate. The massive consumption of wood depleted the forests very quickly and caused the glassworks to

go out of business. The ruling landowners now established the hammer-works which arised at each suitable

watercourse. (Additional water-mills also could be found in Wintersbach, Lichtenau, Waldaschaff and Laufach.)

If you hike from the village of Hasloch into the Spessart, then you can hear from time to time

the metallic knocking of the iron-hammer-works. It is the last iron-hammer-works in the Spessart that still today

can be operated as a

»hydro-power station« with its technical installation dating back to the founding period (year of construction 1779).

This hammer-works is the beginning of the iron factory Kurtz in Hasloch am Main.

Its creation owes the hammer-works to the abundance of trees found in the nearby forests and the waterpower supplied by the

Haselbach (hazel creek), which originates in the Spessart beneath Rohrbrunn. This area formerly

belonged to the Electors of Mainz, who had planned some sort of industrializing of the remote areas of the Spessart

and the Odenwald. Initially, they developed the glassworks which required an immense quantity of wood and charcoal

to operate. The massive consumption of wood depleted the forests very quickly and caused the glassworks to

go out of business. The ruling landowners now established the hammer-works which arised at each suitable

watercourse. (Additional water-mills also could be found in Wintersbach, Lichtenau, Waldaschaff and Laufach.)

The foundation day of the Hasloch "iron-hammer-works" is March 24, 1779. On this day, the three earls of Loewenstein-Wertheim have issued an inheritance document to guarante the brothers Tobias and Johann Heinrich Wenzel from Neulautern the ground for the building of an iron-hammer-works.

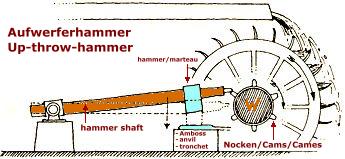

The building for housing the iron-hammer-works was constructed about 3 km north of the village Hasloch on the Haselbach, about a hundred meters further uphill ditch was duged in which the water was stored and funneled to the water-wheel. At the end of the water construction are the »overshot water-wheels«, which drive the iron-hammers. Originally four iron-hammers were operated, of which two still are preserved: an up-throw-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer") and a so-called tail-hammer ("Schwanzhammer").

When the smith pulled the "sluice gate" by means of an iron-rod, a slide-valve opened in the water building which allowed the water to fall freely into the paddles and the water-wheel turned the main shaft (an oak trunk of approx. 9 m of length and 80-90 cm of diameter). Inside the hammer building, at the other end of the main shaft, is a strong cast iron ring with five cast cams on which wooden blocks (the so-called "frogs") attached. When the waterwheel turns, the cams raise the "Aufwerferhammer", which is attached in a scaffold parallel to the main shaft and the bear (the hammer head is called bear) falls down due to its own weight (170 kg). Thereby the red-hot iron lying on the anvil is deformed. This process repeates itself by each contact with a cam. The smith can readily adjust the rate of the successive hammer strokes by regulating the flow of the quantity of water. When he closes the sluice gate, the operation will terminate. The up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer") has been in operation for 200 years and is still working today with all the original mechanisms. original mechanisms.

Under this up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer") in former times the so-called balls ("Luppen") were out-forged.

This were iron lumps of approximately 150 pound, which were melted from scrap-irons in a puddel-oven with charcoal. From the out-forged

ball-iron were made agricultural commodities: carriage hoops, carriage axles, wheel shoes, plowshares, crowbars and other forgings.

Under this up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer") in former times the so-called balls ("Luppen") were out-forged.

This were iron lumps of approximately 150 pound, which were melted from scrap-irons in a puddel-oven with charcoal. From the out-forged

ball-iron were made agricultural commodities: carriage hoops, carriage axles, wheel shoes, plowshares, crowbars and other forgings.

The up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer") is already in operation for 200 years.

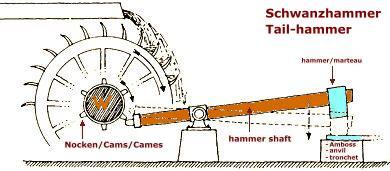

The smaller hammer is called "tail-hammer" ("Schwanzhammer") because the cams press the tail of the hammer-shaft,

and as a result, cause the lifting of the hammer. This smaller hammer also has a cast-iron ring with 15 cams on the

drive shaft, which cause a much faster impact sequence of the hammer. The hammer-head (135 kg) is lighter than the

large up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer"). This hammer was used to forge about 40,000 to 50,000 plowshares annually.

Here the smith sits on a hanging, movable stool making his work substantially easier.

The smaller hammer is called "tail-hammer" ("Schwanzhammer") because the cams press the tail of the hammer-shaft,

and as a result, cause the lifting of the hammer. This smaller hammer also has a cast-iron ring with 15 cams on the

drive shaft, which cause a much faster impact sequence of the hammer. The hammer-head (135 kg) is lighter than the

large up-thrower-hammer ("Aufwerferhammer"). This hammer was used to forge about 40,000 to 50,000 plowshares annually.

Here the smith sits on a hanging, movable stool making his work substantially easier.

The pieces of iron were heated up in the opposite furnaces until white-hot. The required high degree of heat is produced with the help achieved of a blower, which is also operated by waterpower. The mechanism is more than 100 years old. Two more hammers ran in former times at a common main shaft. Here they forged hoes and picks, which were sharped and polished in the neighboring Barthels mill. In the earlier years the above-mentioned self-melted puddel-iron was processed. When the blast furnaces appeared, bar iron or wrought iron and billet-iron were purchased.

The accommodations for the hammer-smiths were on top of the hammer-works. In the heyday of the iron- hammer-works industry 16 hammer-smiths were kept busy in shift work. Under their leather-loincloth they wore only a light shirt, on their feet wooden clogs and on their head a large floppy hat.

The iron-hammer-works in the Odenwald and Spessart slowly were silenced one after another in the 19th Century due to outside influence. In essence, they had to give way more modern production methods and technical advances and consequently were displaced by the new blast furnaces of the Ruhr district.

The iron-hammer-works Hasloch continues to be operated by Kurtz Ersa Corporation for reasons of tradition and is part of the iron-hammer museum on the grounds. The iron-hammer museum and the historic iron-hammer-works convey "Living Technology since 1779". The exhibition shows 240 years of corporate and industrial history: from the beginnings of the iron-hammer with its forged products to the international Kurtz Ersa Group today. At many have-a-go stations you can become active yourself. Experience how water power can be regulated or how to solder a radio circuit! Many exciting exhibits and graphs provide entertainment for the whole family.

Do you want to witness how how one forged formerly ?

Then a visit is worthwhile !

Contact:

Kurtz Ersa HAMMERMUSEUM

Eisenhammer

97907 Hasloch

Opening hours:

March - October

Wednesday - Sunday & Holidays: 10:00 - 16:00

November

Friday - Sunday: 10:00-16:00

December - February: closed

Phone: 49 9342 805459

E-mail: info(at)hammer-museum.de

Web: www.hammer-museum.de

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kurtzersa.hammermuseum/

See Youtoube-Video: The iron-hammer-works in Hasloch - a living industry monument

Welcome in the beautiful Hasloch-valleyFr, Dez 20 2019 02:17:27